A condensed account of testing and verification between 1911 and 1922,

with particular attention to Lick Observatory’s role

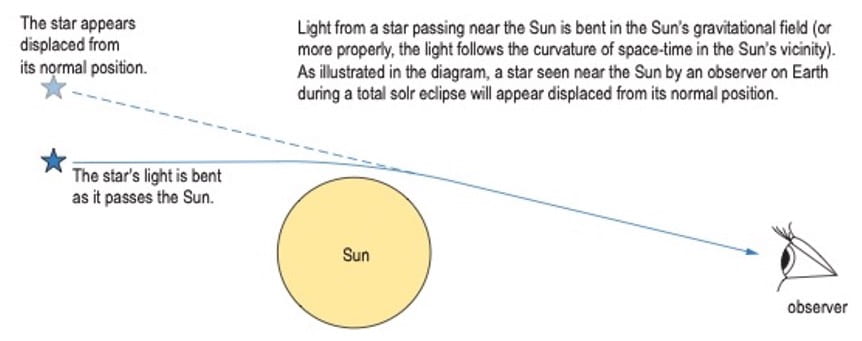

In 1911, with his General Theory of Relativity still a work in progress, Einstein published several predictions the theory had already led to, along with tests by which they might be proven or disproven. One of the theory’s important predictions was that light, like matter, is subject to gravity, and that the normally straight path of a light ray traveling through empty space would be bent in the presence of a large mass. Einstein reasoned that if his theory was correct, starlight passing near the Sun would be bent, thereby slightly shifting a star’s apparent position as seen by an observer on Earth. The maximum size of the predicted shift was small—less than the apparent size of a dime seen from 2.5 miles away—but potentially measurable. (The size of the shift was doubled in the final theory, but still miniscule.)

Of course, stars are not normally visible near the Sun, their light being drowned out by the Sun’s much greater brilliance. But there is an exception: during a total solar eclipse, when the Sun is briefly hidden behind the Moon, bright stars can be observed in its vicinity. Einstein urged astronomers to test his theory. This would require photographing stars near the Sun during eclipse and measuring their apparent positions compared to the same stars photographed at night.

By the time Einstein proposed his scheme to test for the deflection of starlight, Lick Observatory was arguably the world leader in eclipse observations. Since 1889 Lick had been sending expeditions to observe total solar eclipses as far away as Chile, Japan, India, Sumatra, Egypt, and the South Pacific. With its long experience, photographic expertise, a suite of specially designed eclipse instruments, and a reliable benefactor to fund its expeditions, Lick was a natural candidate to conduct the Einstein observation. But in 1911, relativity theory was not widely known—much less understood—outside the German physics community, and Einstein’s test would have been at best a blip on Lick’s radar.

Meanwhile, in Berlin, Erwin Findlay-Freundlich, a mathematically trained astronomer with a keen interest in Einstein’s theory, wondered whether the necessary data might already exist on photographs taken at earlier eclipses. In 1912 he turned to Lick Observatory’s director, William Wallace Campbell, for help. Campbell agreed to provide Freundlich with copies of Lick’s eclipse photographs, despite reservations about their suitability for the difficult measurement.

In the end, as Campbell suspected, the photographs were inadequate to the task. But his interest in the observational challenge of the Einstein test had been kindled. A Lick expedition to Russia for the 1914 eclipse was already in the works; adding the Einstein test to the regular eclipse program would be a worthwhile extracurricular observation, for which Lick already had instruments that could be suitably adapted.

In the event, the Russian observations were lost to clouds and no photographic plates were obtained. Overshadowing this disappointment was the outbreak of World War I, which found the Lick party behind Russian lines and witness to the mobilization of Russian troops. The party escaped through Scandinavia but had to leave its instruments in care of the Pulkovo Observatory in St. Petersburg.

Another Lick expedition attempted the Einstein test at the 1918 eclipse in nearby Washington State. The Lick eclipse instruments, though by then on their journey home from Russia, did not arrive in time, and a makeshift Einstein Camera had to be constructed from spare and borrowed parts. Photographic plates were obtained, but the cameras’ imperfect mounting, mismatched lenses, and optical aberrations produced defective star images that would prove troublesome.

Lick astronomer Heber D. Curtis was assigned the slow and painstaking task of measuring the plates and making the attendant computations. In the Spring of 1919—despite high probable errors in the measures, he confidently told Campbell that the plates showed no evidence to support general relativity. Despite Curtis’s faith in his conclusion, Campbell became increasingly uneasy with it. When he reported Curtis’s results to a meeting of the Royal Astronomical Society in London in July,

he did so guardedly.

Though the 1919 eclipse was particularly favorable to the Einstein test—the eclipse being of unusually long duration and the Sun surrounded by a rich field of stars—Campbell had chosen not to mount a Lick expedition. The British, however, dispatched two parties, one to Brazil, the other to the island of Principe off the west coast of Africa. Their preliminary measures favored Einstein’s theory and were read at the same meeting where Campbell had just cautiously reported Lick’s 1918 results.

On Principe, clouds had interfered on eclipse day, and only two of the 16 plates exposed showed measurable stars. The sky was clear in Brazil, but though full sets of plates were obtained with each of that party’s two cameras, one set was badly compromised by optics overheating in the sun. Measures of the star images on the Principe plates and the unflawed Brazil plates gave results in good agreement with Einstein; measures of the flawed Brazil plates showed a stellar shift, but only about half as large as was required by General Relativity.

The press leapt on the British announcement, and Einstein became an overnight celebrity. Campbell telegrammed Curtis, ordering him to halt publication of the Goldendale results.

The clamorous public reception of general relativity notwithstanding, the British results were met with mixed reviews in the scientific community. The theory was so difficult to understand and its implications so unsettling that skepticism was inevitable; and the British data were, in any case, imperfect. Unequivocal observations showing whether stellar deflection was real—and, if so, whether in the amount predicted by Einstein’s theory—remained to be done.

Campbell was a classically trained astronomer who would have preferred the more familiar and accessible Newtonian model of the universe, but his scientific integrity demanded a definitive test. He was intent that Lick astronomers be the ones to provide incontrovertible data, one way or the other. Though he had earlier indicated that the next Lick expedition would not be until 1923, when an eclipse would be visible from nearby Southern California and Mexico, he now set his sights on the upcoming 1922 eclipse visible in Australia, with the Einstein problem as its central mission.

Campbell commissioned two matching pairs of purpose-designed cameras and sent them to Tahiti months in advance, in the charge of Lick staff astronomer Robert Trumpler, to take nighttime comparison photographs of the stars that would be visible near the Sun at the eclipse. The Lick party subsequently made its camp along a remote stretch of coast at Wallal, in northwest Australia, where clear weather was all but guaranteed.

The conditions on eclipse day were perfect, and excellent plates were obtained showing hundreds of measurable stars. Examining the star images when back home at Lick Observatory, Trumpler’s measurements showed stellar deflection in excellent agreement with Einstein’s prediction. The Lick results provided the unequivocal confirmation of general relativity needed to convince the scientific community that they must accept a rich and strange new model of the universe.